Verichips are implanted in the upper arm of patrons at the Baja Beach Club in Barcelona, Spain. Along with the Baja Beach Club is The Rotterdam Beach Club in the Netherlands, and the Bar Soba in Glasgow, Scotland, all who have successfully introduced the Verichip microchip implant as a form of payment.

"Beautiful club-goers have a problem: If you're going to wear a halter top and micro-skirt, there's not much of anywhere to put a wallet. And who wants to carry a purse when you're there to dance? Luckily, a company called VeriChip this year unveiled a solution based on radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology. It's a slender glass capsule ... a computer chip, which stores a unique code that can identify an individual — sort of an electronic Social Security number." Get chipped, then charge without plastic -- you are the card!!!!!!!

VeriChip is the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved human-implantable radio-frequency identification (RFID) microchip. It is marketed by VeriChip Corporation, a subsidiary of Applied Digital Solutions, and it received United States FDA approval in 2004. About twice the length of a grain of rice, the device is typically implanted above the triceps area of an individual’s right arm.[citation needed] Once scanned at the proper frequency, the VeriChip responds with a unique 16 digit number which could be then linked with information about the user held on a database for identity verification, medical records access and other uses. The insertion procedure is performed under local anesthetic in a physician's office and once inserted, is invisible to the naked eye. As an implanted device used for identification by a third party, it has generated controversy and debate.

Destron Fearing, a subsidiary of Applied Digital Solutions, initially developed the technology for the VeriChip.[1]

In the beginning of 2007, Verichip Corporation created Xmark, its corporate identity for healthcare products. Xmark incorporates the Hugs and the Halo system of infant protection; the RoamAlert system of wandering protection; the MyCall emergency response system; and the Assetrac asset tracking system.

Privacy

Privacy advocates have protested the VeriChip, warning of potential abuse and denouncing these types of RFID devices as "spychips," and that use by governments could lead to an increased loss of civil liberties and would lend itself too easily to abuse. Among Communist countries and dictatorships authoritarianism historically has been more obvious, but such concerns were justified in the United States, when the CIA program COINTELPRO was revealed to have tracked the activities of high profile political activist and dissident figures. There is also the possibility that the chip's information will be available to those other than governments, such as private business, thus giving employers highly personal information about employees. In addition, privacy advocates state that the information contained in this chip could easily be stolen, so that storing anything private in it would be to risk identity theft. As the human-implantable microchip only contains a unique 16-digit electronic identifier, the unique number is used only for such purposes as accessing personal medical information in a password-protected database or assessing whether somebody has authority to enter into a high-security area. Although the company that makes VeriChip claims that it does not contain any other information beyond this unique 16-digit number, it could be scanned and used to access the database.[2]

Security

Anyone possessing a VeriChip reader can read the human-implantable RFID microchip; the data is unencrypted, and VeriChip does not have the functionality to authorize only certain people to read it. Being a passive RFID microchip containing only a unique 16-digit identifier it can be read by a VeriChip reader held up closely to the location of the inserted chip. This concern can be partially mitigated by using such a chip without implanting it, as by inserting it into the wristband of a watch, which can then be removed at will.

The database associated with the device currently contains only health related information, with no financial information or social security number being stored. The information itself is controlled and directed by the subscriber.

Specifically because it is technically possible to extract the information on a VeriChip, the chip contains only a nondescript 16 digit number. To access the associated personal health record of a subscriber, one must possess a secure logon that is provided only to participating medical facilities, and a record is made every time anybody logs on and accesses a subscriber's record.

An implanted VeriChip was cloned in January 2006 as a demonstration; instructions for cloning VeriChips are available on the web.[3][4]

Health Risks

According to Wired News online[5], and the Associated Press[6], there have been research articles over the last ten years that found a connection between the chips and possible cancer. When mice and rats were injected with glass-encapsulated RFID transponders, like those made by VeriChip, they "developed malignant, fast-growing, lethal cancers in up to 1% to 10% of cases" at the site at which the microchip was injected or to which it had migrated. However, the 10% rate was obtained with hemizygous p53-deficient mice, the counterpart of humans with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and rates near 1% were more typical.[7] The Verichip corporation responded to this report, which caused a 40% drop in their stock value, by stating that rodent data had been provided to the FDA and did not reflect the effect of the chips in humans or pets.[8] Rather, rodent foreign body sarcomagenesis is a unique reaction, as evidenced by the publication of only two isolated cases from the large number of dogs subjected to chip implantation. Induction of sarcomas by foreign bodies has been reported in humans,[9][10][11][12][13][14] and has been described as analogous to rodent foreign body-associated sarcomas, but occurring rarely. Resolution of the question may be hindered by the long delay in onset of rare effects, as in the case of other medical controversies regarding foreign objects such as the breast implant controversy and the risk of non-occupational asbestos exposure.

Religious Concerns

Privacy advocates have protested the VeriChip, warning of potential abuse and denouncing these types of RFID devices as "spychips," and that use by governments could lead to an increased loss of civil liberties and would lend itself too easily to abuse. Among Communist countries and dictatorships authoritarianism historically has been more obvious, but such concerns were justified in the United States, when the CIA program COINTELPRO was revealed to have tracked the activities of high profile political activist and dissident figures. There is also the possibility that the chip's information will be available to those other than governments, such as private business, thus giving employers highly personal information about employees. In addition, privacy advocates state that the information contained in this chip could easily be stolen, so that storing anything private in it would be to risk identity theft. As the human-implantable microchip only contains a unique 16-digit electronic identifier, the unique number is used only for such purposes as accessing personal medical information in a password-protected database or assessing whether somebody has authority to enter into a high-security area. Although the company that makes VeriChip claims that it does not contain any other information beyond this unique 16-digit number, it could be scanned and used to access the database.[2]

Security

Anyone possessing a VeriChip reader can read the human-implantable RFID microchip; the data is unencrypted, and VeriChip does not have the functionality to authorize only certain people to read it. Being a passive RFID microchip containing only a unique 16-digit identifier it can be read by a VeriChip reader held up closely to the location of the inserted chip. This concern can be partially mitigated by using such a chip without implanting it, as by inserting it into the wristband of a watch, which can then be removed at will.

The database associated with the device currently contains only health related information, with no financial information or social security number being stored. The information itself is controlled and directed by the subscriber.

Specifically because it is technically possible to extract the information on a VeriChip, the chip contains only a nondescript 16 digit number. To access the associated personal health record of a subscriber, one must possess a secure logon that is provided only to participating medical facilities, and a record is made every time anybody logs on and accesses a subscriber's record.

An implanted VeriChip was cloned in January 2006 as a demonstration; instructions for cloning VeriChips are available on the web.[3][4]

Health Risks

According to Wired News online[5], and the Associated Press[6], there have been research articles over the last ten years that found a connection between the chips and possible cancer. When mice and rats were injected with glass-encapsulated RFID transponders, like those made by VeriChip, they "developed malignant, fast-growing, lethal cancers in up to 1% to 10% of cases" at the site at which the microchip was injected or to which it had migrated. However, the 10% rate was obtained with hemizygous p53-deficient mice, the counterpart of humans with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and rates near 1% were more typical.[7] The Verichip corporation responded to this report, which caused a 40% drop in their stock value, by stating that rodent data had been provided to the FDA and did not reflect the effect of the chips in humans or pets.[8] Rather, rodent foreign body sarcomagenesis is a unique reaction, as evidenced by the publication of only two isolated cases from the large number of dogs subjected to chip implantation. Induction of sarcomas by foreign bodies has been reported in humans,[9][10][11][12][13][14] and has been described as analogous to rodent foreign body-associated sarcomas, but occurring rarely. Resolution of the question may be hindered by the long delay in onset of rare effects, as in the case of other medical controversies regarding foreign objects such as the breast implant controversy and the risk of non-occupational asbestos exposure.

Religious Concerns

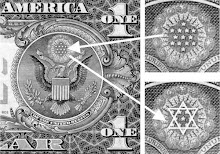

Some Christians have come out against the device, as there is a Biblical prophecy where all persons must receive the Mark of the Beast "on their right hand or on their foreheads", described in Book of Revelation 13:16-18, to participate in economic activity under the government of the Antichrist.[15] This concern is compounded by the fact that, according to a recent ABC News article, there have been reports of other chips being implanted in patients' right hands. However, the chip has also been seen being implanted in the left arm or hand as well as other areas.[16] It is often surmised that the sixteen digits in the chip stand for the last digits of 666, the original Mark of the Beast. The Greek word Charagma (which stands for 666) describes the piercing bite of a snake, which is akin to using a needle to place the device under your skin.[17]

In addition, there are various religions and sects which abhor the penetration of the human body, as with surgery or the implantation of devices. An implanted VeriChip violates the mores of such groups.

The Album "Genesis" by the American Heavy metal band Job for a Cowboy describes the controversy between the VeriChip producers and Religious institutions, fictionally describing such events as religious Conspiracy and the rise of the Antichrist.

Proponents

Tommy Thompson, the former Secretary of Health and Human Services, along with other experts supports the VeriChip as a "useful tool in sharing medical information with health care providers in emergency situations". Thompson also sits on the board of directors of VeriChip's parent company Applied Digital Solutions. In June of 2007, the American Medical Association declared that "implantable radio frequency identification (RFID) devices may help to identify patients, thereby improving the safety and efficiency of patient care, and may be used to enable secure access to patient clinical information". [18]

Opponents

Privacy advocates Katherine Albrecht and Liz McIntyre are the most prominent opponents of implanted microchips. They are coauthors of a position paper on the use of spychips, "RFID: The Big Brother code, the books "Spychips: How Major Corporations and Government Plan to Track Your Every Move with RFID" (2006) and "The Spychips Threat: Why Christians Should Resist RFID and Electronic Surveillance" and the Antichips.org website. Their work broadly overlaps that of CASPIAN, a grassroots privacy group founded by Albrecht in 1999 to oppose the use of "loyalty cards" to track consumer purchases in supermarkets. Associated sites include Spychips.org, a site opposing RFID chips hidden in consumer goods, and Nocards.org, with more general discussion of privacy issues. Notable quotes include McIntyre (on the VeriChip liability waiver for product failure) "I wouldn't buy toilet paper that required that kind of a disclaimer, never mind a product that's supposed to serve as a lifeline in an emergency.", and Albrecht: "A man with a chip in his arm may soon find himself wondering whether that cute gal on the next bar stool likes his smile or wants to clone his VeriChip. It gives new meaning to the burning question, 'Does she want my number'?"

Competitors

Competitors for VeriChip RFIDs in implantable medical identification devices are Smart Tokens by Datakey Inc.[19] or micoID(TM) by MicroChip Inc.[20][21] The use of any external marking, such as a tattoo, to indicate the presence or original location of a Verichip under the skin is subject to US patent 2003/195523

In addition, there are various religions and sects which abhor the penetration of the human body, as with surgery or the implantation of devices. An implanted VeriChip violates the mores of such groups.

The Album "Genesis" by the American Heavy metal band Job for a Cowboy describes the controversy between the VeriChip producers and Religious institutions, fictionally describing such events as religious Conspiracy and the rise of the Antichrist.

Proponents

Tommy Thompson, the former Secretary of Health and Human Services, along with other experts supports the VeriChip as a "useful tool in sharing medical information with health care providers in emergency situations". Thompson also sits on the board of directors of VeriChip's parent company Applied Digital Solutions. In June of 2007, the American Medical Association declared that "implantable radio frequency identification (RFID) devices may help to identify patients, thereby improving the safety and efficiency of patient care, and may be used to enable secure access to patient clinical information". [18]

Opponents

Privacy advocates Katherine Albrecht and Liz McIntyre are the most prominent opponents of implanted microchips. They are coauthors of a position paper on the use of spychips, "RFID: The Big Brother code, the books "Spychips: How Major Corporations and Government Plan to Track Your Every Move with RFID" (2006) and "The Spychips Threat: Why Christians Should Resist RFID and Electronic Surveillance" and the Antichips.org website. Their work broadly overlaps that of CASPIAN, a grassroots privacy group founded by Albrecht in 1999 to oppose the use of "loyalty cards" to track consumer purchases in supermarkets. Associated sites include Spychips.org, a site opposing RFID chips hidden in consumer goods, and Nocards.org, with more general discussion of privacy issues. Notable quotes include McIntyre (on the VeriChip liability waiver for product failure) "I wouldn't buy toilet paper that required that kind of a disclaimer, never mind a product that's supposed to serve as a lifeline in an emergency.", and Albrecht: "A man with a chip in his arm may soon find himself wondering whether that cute gal on the next bar stool likes his smile or wants to clone his VeriChip. It gives new meaning to the burning question, 'Does she want my number'?"

Competitors

Competitors for VeriChip RFIDs in implantable medical identification devices are Smart Tokens by Datakey Inc.[19] or micoID(TM) by MicroChip Inc.[20][21] The use of any external marking, such as a tattoo, to indicate the presence or original location of a Verichip under the skin is subject to US patent 2003/195523

No comments:

Post a Comment